Now With 100% Less Whining

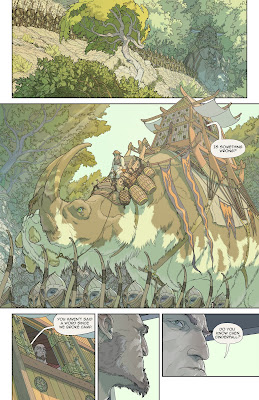

Page 4 first-pass color complete. Click to enlarge. More below. Here's why I love the internet: a month ago, I didn't know the word "flatting." Three weeks ago, I didn't know there were flatting plugins. Two weeks ago, it took me fifteen hours to flat a page using those plugins. This week, it took three hours. All because of comments on this blog. Holy shnikeys. I ended up trying Eagle's method -- that is, removing extraneous lines from the line art layer before running the plugins. Below are examples of the line art for this page in pre- and post-culled states. Note that in many cases all I had to do was make a "leak" in between two areas so that they filled with the same color. And here's what the plugins spat out. The second image is cleaner and more tractable. All it needs is a few dinks with the magic wand, and I'm on my way. By the way, I still used the high-noise version at left to add some nice random variation to large single-color a...